STRUCTURES Blog > Posts > The Origins of Black Hole Mergers: Diverse Pathways Across the Universe

The Origins of Black Hole Mergers: Diverse Pathways Across the Universe

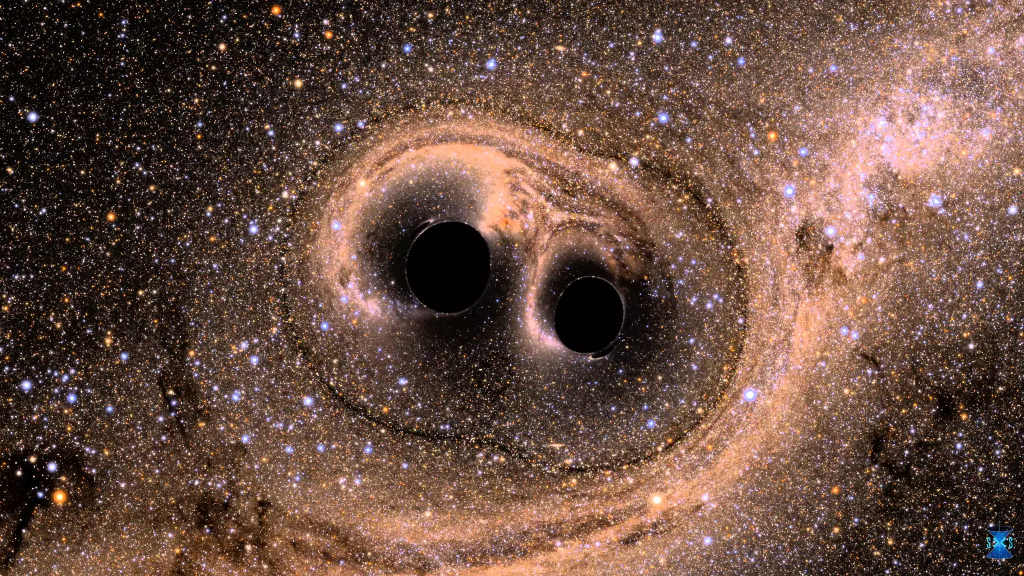

The merger of two black holes is one of the most extreme and yet fascinating events in the Cosmos. When two black holes coalesce, they release a tremendous amount of energy in the form of gravitational waves. These ripples in spacetime can be captured by high-precision detectors on Earth, and provide key insights into the nature of black holes, the galaxies they live in, and the Universe’s history.

Gravitational Waves: An Ear on the Cosmos

Before the first observation of gravitational waves in 2015, the Universe could only be studied through photons (i.e., light and other electromagnetic waves) and neutrinos (tiny, nearly massless particles). Gravitational waves represent the third messenger of our Universe, complementing the information we gather from photons and neutrinos. These waves are ripples in space-time travelling at the speed of light, with possible frequencies spanning an astonishing range of twenty orders of magnitude. The gravitational-wave frequencies detectable from Earth range from a few tens to several thousand Hertz, approximately the same range as the human voice. In contrast to photons, which allow us to observe the light emitted by stars and galaxies, detecting gravitational waves enables us to “listen to the sound” of objects that would otherwise remain dark and invisible, such as black holes.

Einstein predicted the existence of gravitational waves in 1915, but it took exactly 100 years to develop the technology required to measure them. Gravitational waves passing through Earth produce tiny deformations in the geometry of space, causing oscillations in the distance between two objects. Such deformations are incredibly small, on the order of one part in a billion trillion (that’s a 1 followed by 21 zeros). To put this into perspective, a gravitational wave event alters the distance between the Earth and the Sun by only the width of a hydrogen atom (around 0.1 nanometres).

Before we were able to detect gravitational waves, we did not know whether black hole pairs actually exist in the Universe. Many scientists were skeptical about the possibility of black hole mergers, as such events require that two black holes form very close to each other, at a distance smaller than about 100 times the radius of our Sun. Today, we have observed more than 100 gravitational wave events, most of them associated with black hole mergers. The possibility of observing binary black hole mergers marks the beginning of a new era in the study of black holes.

The Simplicity of a Black Hole, and the Complexity of its Formation

It might seem a paradox, but astrophysical black holes are simple objects: they are completely described by two quantities, their mass and their spin. The spin quantifies the black hole’s rotation around its own axis. From gravitational wave observations, we can derive both quantities.

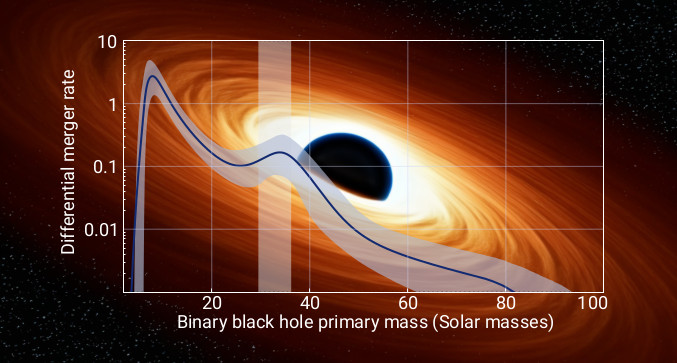

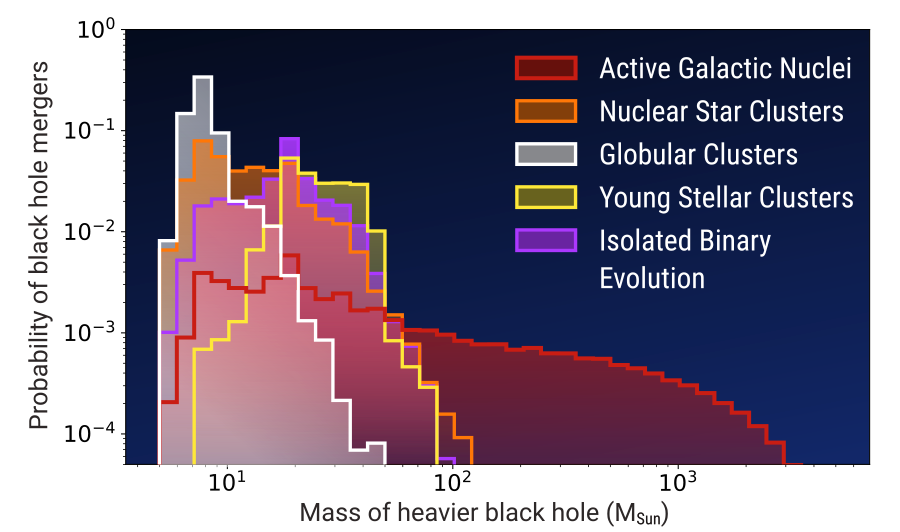

Particularly, we can now start to reconstruct the mass function of black holes. As shown in Fig. 1, the observed black hole mass function shows three clear structures: two prominent peaks at 10 and 35 solar masses, respectively, and a long tail extending up to almost 100 solar masses. These structures tell a story about the origin of black holes and the environment they inhabit.

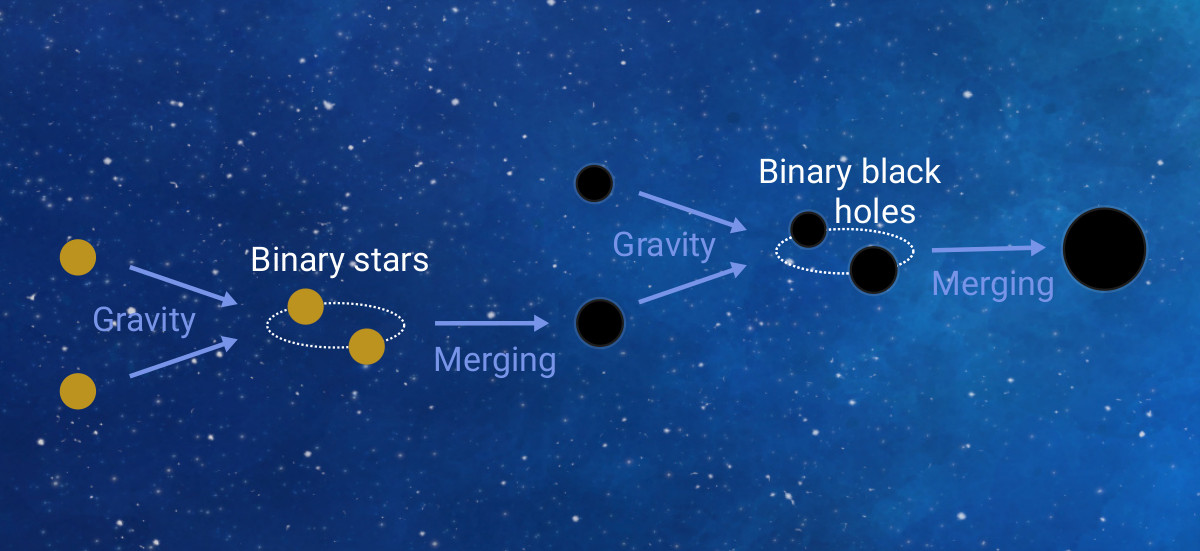

Binary black hole systems can form in one of two ways: they can either be original binaries or dynamically assembled binaries. An original binary black hole results from the evolution of a binary of two massive stars, where the stars undergo so-called core collapse and create black hole remnants unless the binary is disrupted by the supernova explosions. In contrast, a dynamically assembled binary black hole forms via encounters of black holes in dense stellar environments, such as stellar clusters.

Taking a Closer Look at the Birthplaces of Binary Black Holes

In a dense stellar environment, a black hole experiences a large number of close-by interactions with other objects (stars, white dwarfs, neutron stars, or black holes), leading to a number of dynamical processes. A binary black hole can form by direct encounters of three single bodies, of which at least two are black holes. Indeed, during the chaotic and resonant evolution of a triple system, there can be very close passages between pairs of objects so that the system loses energy through gravitational wave production, and the formation of a binary is favoured.

If the environment is dense enough, after two black holes merge, the resulting larger black hole can stay in the system, find another partner, and merge again. This second (or higher) generation of mergers is known as hierarchical mergers, and their study is crucial to understanding the black hole population.

For Advanced Readers: Energetics in Dynamical Assembly of Binary Black Holes

Interested in mathematical details? Click here to expand this section!

The total energy $E$ of two bodies with masses $m_1$ and $m_2$ at a distance $r$ moving with relative velocity $v$ is the sum of their kinetic energy $T$ and gravitational potential energy $U$:

$$ E=T+U. $$

Defining the so-called reduced mass, $\mu=m_1 m_2/(m_1 + m_2)$, in the centre of mass frame, the kinetic and potential energy of can be expressed as:

Hence, the total energy is the sum of a positive term, $T$, and a negative term, $U$. The kinetic energy arises from the motion of the bodies, which tends to drive them apart, while the gravitational potential energy comes from their mutual gravitational attraction, which pulls them together.

We can say that two bodies are bound in a binary system if $E<0$, that is to say that the gravitational potential energy dominates over the kinetic energy. In this case, the two bodies cannot escape each other and are forced to orbit their common centre of mass. Intuitively, you can think of the gravitational potential as a “well” that the system falls into: if the system doesn’t have enough total energy to climb out, the bodies remain trapped together. Conversely, if $E\geq0$, the kinetic energy is sufficient to overcome the gravitational pull, and the system is unbound. In this case, the two bodies might approach each other briefly but will eventually separate, never forming a stable binary.

If two unbound bodies come close enough to each other, they emit a significant amount of gravitational waves, which carry away some of the system’s total energy. This decreases the total energy of the system and favours the transition from an unbound state ($E\geq 0$) to a bound binary system ($E<0$).

We can name several environments that can give rise to the dynamical assembly of binary black holes.

But first, what makes each environment different?

-

Active Galactic Nuclei (AGN) disks are dense regions of gas around supermassive black holes in the centres of some galaxies, and their gas plays a crucial role in bringing smaller black holes together because it acts like a brake, slowing down and shrinking the orbits of black hole pairs, until they eventually collide and merge.

-

Star clusters are dense stellar environments. Their dynamics allow black holes to find partners through gravitational interactions. Each type of cluster has its quirks:

- Nuclear Star Clusters: Found near galactic centres, they host massive numbers of stars and black holes. They have typical masses between ten thousand and a billion solar masses and typical ages of a few billion years.

- Globular Clusters: Older and more evolved, they are less massive than nuclear clusters, but still dense. They are typically more than ten billion years old (for scale, the Universe itself is approximately 14 billion years old) and their mass ranges between ten thousand and a million times the mass of our Sun. They are quite compact and typically found in the outskirts of galaxies.

- Young Star Clusters: As the name suggests, these are young stellar nurseries with fewer stars but active black hole formation. They have ages of about one hundred million years (quite short for astrophysical timescales!) and they are gravitationally loose. They have typical masses of one hundred to one hundred thousand times the mass of the Sun.

For Curious Readers: The Effect of AGN Disks on Black Hole Dynamics

When black holes exist in an Active Galactic Nucleus (AGN), their orbits can cross the dense gaseous disk and be subject to strong gas drag. This slows down the movement of these black holes, just like swimming through a thick liquid – like honey – offers more resistance than swimming through water. The final effect is that the inclination and the eccentricity of their orbit are damped, so after a sufficient number of laps they will have circular orbits embedded in the disk.

Once a black hole’s orbit becomes embedded in a disk of gas, it interacts gravitationally with the surrounding material creating waves, or density wakes, in the gas. In turn, the gravitational pull from these wakes exerts forces on the object. These forces are called gas torques.

If the torques are unbalanced (i.e. stronger on one side of the orbit than the other) they can cause the object to migrate through the disk. This process is known as migration. We can think of it as the black hole being “tugged” by the waves it stirs up in the gas, like a boat being pulled by ripples it creates on a lake.

Gas torques can be unbalanced in both ways, meaning that migration can proceed either outwards or inwards depending on the specific conditions in the disk. More specifically, the direction of torques is thought to vary depending on the region of the disk: migration is generally directed outwards in the inner disk and inwards in the outer disk. At the boundary between inwards and outwards migration, black holes stop migrating and accumulate in large numbers. These regions, known as migration traps, become hotspots where black holes can efficiently pair up and form binaries.

Such a binary is surrounded by the dense gas of the disk, which once again acts like a brake. This causes the binary to lose angular momentum over time, pulling the two black holes closer together. This process, called hardening, makes the orbit of the binary shrink and tighten, bringing the black holes closer and closer until they eventually merge.

If we also account for the possibility of Isolated Binary Evolution, where two stars evolve together as a binary system and eventually form black holes that merge without much outside interference, this gives us five different ways in which a binary black hole can be formed. We refer to these possible pathways as formation channels.

Why is This Important?

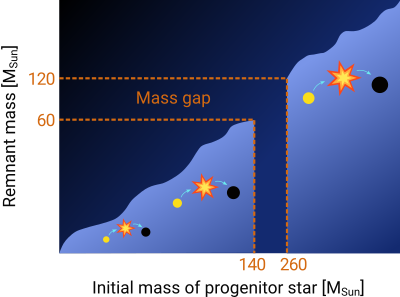

Stellar-mass black holes are thought to form directly from the collapse of massive stars (with initial mass larger than around 20 times that of the Sun). The theory of stellar evolution predicts a gap in black hole masses between approximately 60 and 120 solar masses, which is referred to as the pair-instability mass gap. Of the gravitational wave events detected so far, 13 events have at least one of the progenitors with mass falling into the pair-instability mass gap. There are two possible explanations for the existence of such black holes: either the traditional models of pair-instability supernovae are wrong and it is actually possible to form black holes in the mass range corresponding to the pair-instability gap from direct stellar collapse, or the formation of these black holes requires hierarchical mergers.

Pair-Instability Mass Gap

Insights From Simulations

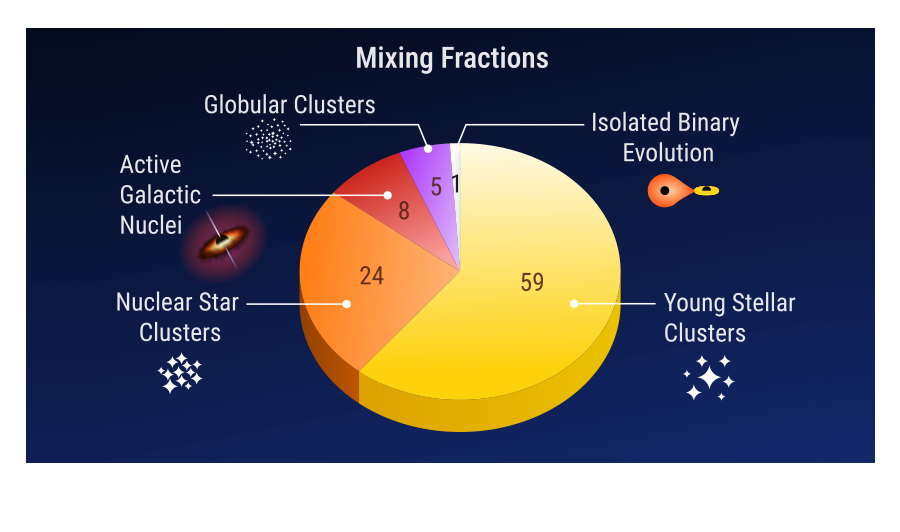

By means of numerical simulations, we can shed light on the formation of black holes with masses in the pair-instability mass gap by comparing predicted outcomes for the mass function in the five main formation channels for binary black hole mergers: Active Galactic Nuclei (AGN) disks, Nuclear Star Clusters (NSCs), Globular Clusters (GCs), Young Star Clusters (YSCs), and Isolated binary evolution (Iso).

Each channel contributes distinctively to the black hole merger population, as illustrated in Fig. 5. In order to quantify the contributions of these channels, researchers use mixing fractions (shown in Fig. 6), which represent the proportion of merger events arising from each channel.

Here’s how our five channels stack up.

Young Stellar Clusters (YSCs) and Nuclear Star Clusters (NSCs) are thought to play a major role in creating the black hole mergers we observe today. Specifically, NSCs tend to form black holes on the smaller side, around 10 times the mass of the Sun, which matches the higher peak seen in gravitational wave data. On the other hand, YSCs are gravitationally looser environments compared to other types of clusters, so they can’t hold onto smaller black holes as tightly and allow them to escape quite easily. As a result, they tend to produce mergers of heavier black holes, closer to 35 times the Sun’s mass, which matches the second peak in the data.

The population of binary black hole mergers produced in Globular Clusters (GCs) falls somewhere in between the mass ranges of NSCs and YSCs. It is interesting to notice how isolated binary evolution (Iso), where black holes form from pairs of stars without external influences, also creates lighter black holes around 10 solar masses, which would match the higher peak in gravitational wave data. However, this channel doesn’t match well with observations of black hole spins and mass ratios, leading to its lower contribution in the analysis.

Finally, Active Galactic Nuclei (AGNs) have the potential to create very massive black holes. However, current detections do not show evidence for mergers of such high-mass black holes, so the AGN channel in found to contribute marginally to the overall merger population.

Conclusions and Future Explorations

In short, by studying the black hole mass spectrum, we not only learn about black holes themselves, but also about complex processes that have shaped our Universe over billions of years. Each binary black hole can tell a story about the environment it came from and the dynamical interactions it has experienced. By observing the different masses of black holes that merge through gravitational waves, we can try to piece together the intricate processes that govern the formation and growth of black holes.

Looking ahead, future gravitational wave observations along with improvements in simulation techniques, will allow us to refine our understanding of these formation channels. As detectors become more sensitive and we collect more data, we’ll be able to distinguish between different pathways of black hole formation with greater precision. This could help us identify which types of environments are most likely to produce certain black hole masses or spins, shedding light on the specific mechanisms at play in these mergers.

In addition, the more we learn about how black holes form and interact, the more we understand the lives of stars themselves. Black holes are born from the collapse of massive stars, and by studying black hole mergers, we also gain insights into the life cycles of these stars, the physics of supernovae, and the ways in which stellar evolution shapes the end states of massive objects. Ultimately, this growing body of knowledge will deepen our understanding of the life and death of stars, the growth of black holes, and the evolution of galaxies — opening doors to new, exciting questions about our Universe.

Tags:

Astrophysics

Gravity

Black Holes

Physics

Galaxies

Stars

Simulations

Structure Formation