STRUCTURES Blog > Posts > How Physicists Are Rethinking Symmetry (Part II)

How Physicists Are Rethinking Symmetry (Part II)

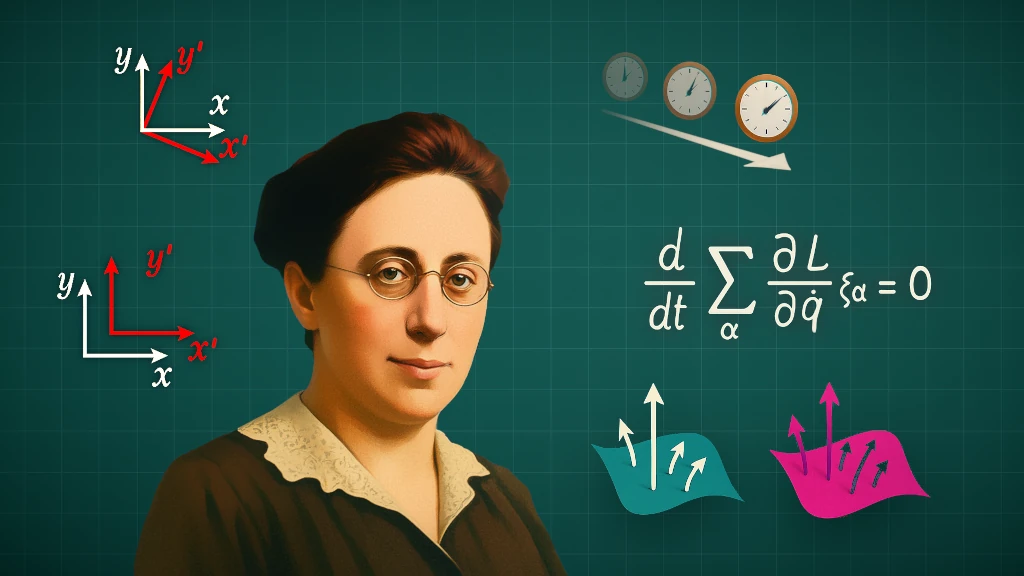

In the first part of this blog series, we explored the concept of symmetries and their foundational role in classical physics, particularly through their deep connection to conserved quantities, a link beautifully captured by Noether’s theorem. In this second part, we shift our focus to quantum field theories (QFTs), a mathematical framework that underpins numerous aspects of modern physics (and mathematics). Symmetries continue to play a central role in this context; they serve, in particular, as distinctive fingerprints that characterize a theory. In recent years, our understanding of symmetry in quantum field theory has broadened dramatically, leading to powerful generalizations that we outline in this article.

To appreciate how symmetries manifest themselves in QFT, however, we must first understand how quantum physics reshaped some of the concepts familiar from classical mechanics in the early 20th century.

The Logic of the Quantum World

The turn of the 20th century marked the beginning of two profound revolutions in our understanding of the physical world. On one side, Einstein’s theories of relativity reshaped our ideas of space, time, and motion – showing that measurements of distance, duration, and even simultaneity depend on the observer’s motion. On the other side, a growing body of experiments revealed that, on very small scales, matter behaved in ways that could not be reconciled with the laws of Newton’s classical mechanics and Maxwell’s electrodynamics. This ultimately led to the development of quantum mechanics, a theory that superseded classical mechanics in the subatomic realm.

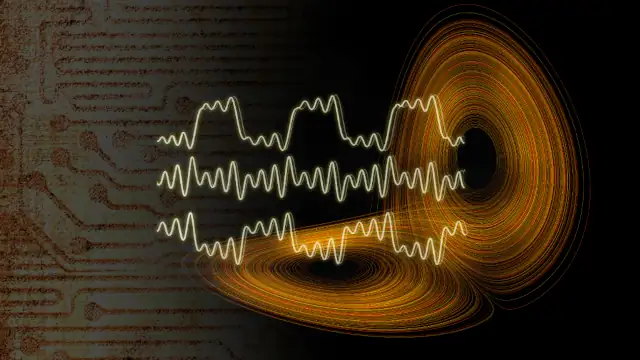

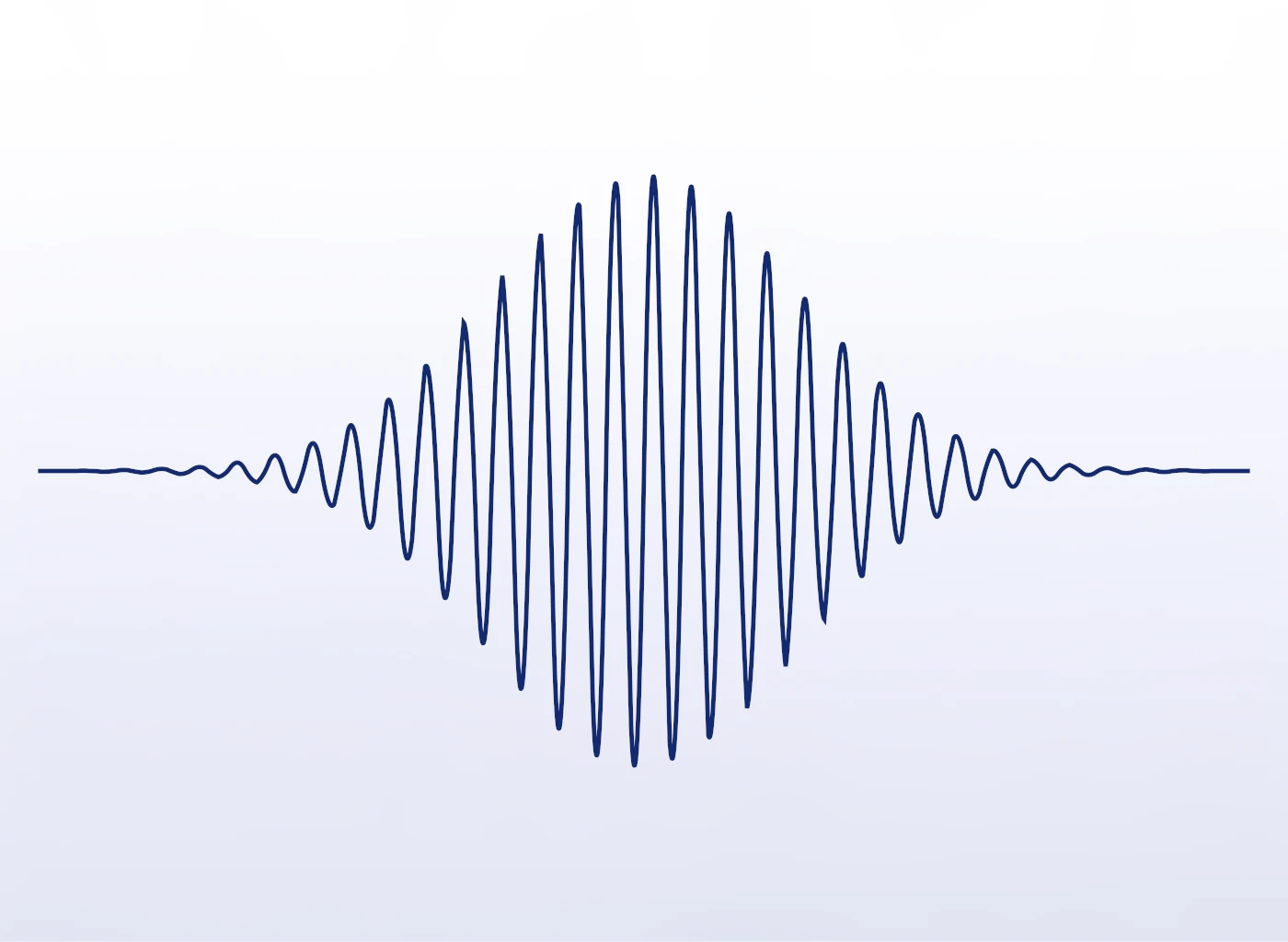

Quantum mechanics is not a mere adjustment of Newton’s laws, but it overturns several foundational assumptions that have long seemed self-evident. Most strikingly, in the quantum world, there are no such things as particles following sharp, predictable paths. By contrast, quantum mechanics describes the probability to find a particle in a given region of space at a given time, encoded in a mathematical object known as the wave function (see an example in Fig. 1). This marks a radical shift away from our classical intuition: quantum particles are not solid marbles evolving in space, but rather fuzzy objects – in the sense that certain properties are not always sharply defined. At microscopic scales, a particle’s position and momentum cannot be simultaneously known with arbitrary precision. This fundamental limitation, known as the Heisenberg uncertainty principle, makes the very idea of a definite trajectory untenable.

This new viewpoint reshaped core concepts of physics. In classical mechanics, a mechanical system is fully described by a point in phase space (introduced in the previous blog post), specifying its exact position and momentum. This is no longer the case in quantum mechanics, where the space of possible positions has to be traded for a so-called Hilbert space of states. Every possible state (or wave function) corresponds to a direction, or “ray,” in this space. This framework embodies one of quantum physics’ most striking and fundamental features: the superposition principle, which has no classical counterpart. This principle states that quantum states can be added, or superposed: just as two arrows can be added to form a new arrow, two quantum states can be combined to form a new valid state. Other mathematical properties of Hilbert space give rise to the Born rule, which specifies how the probabilities inherent to measurements in quantum physics are computed (cf. the info box below, as well as Fig. 2).

Born Rule

Quantum physics offers a fundamentally different perspective on nature compared to classical physics. This naturally raises an important question: what becomes of conservation laws in the quantum world? Does Noether’s theorem still apply, and if so, in what form?

Quantum Field Theories

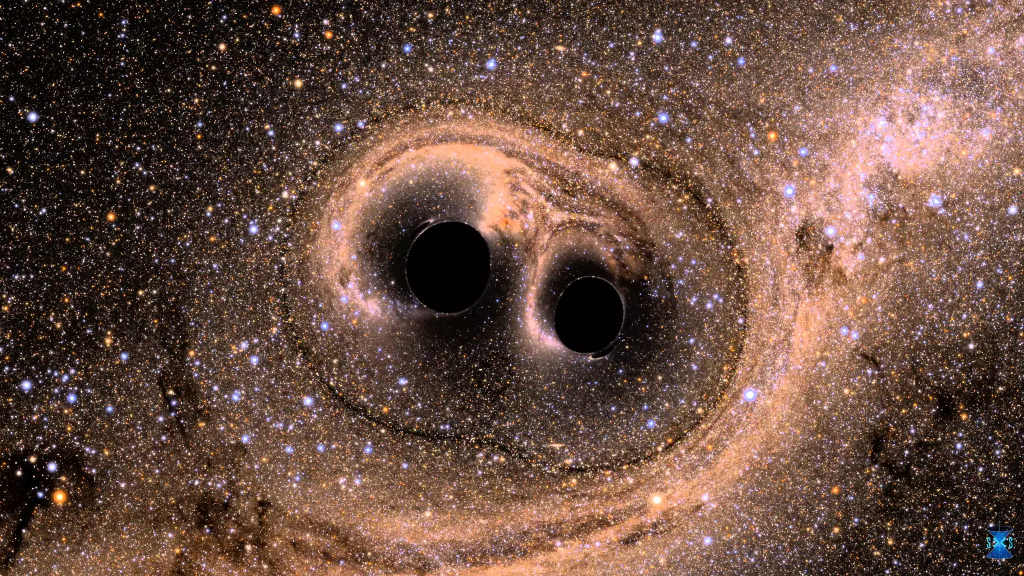

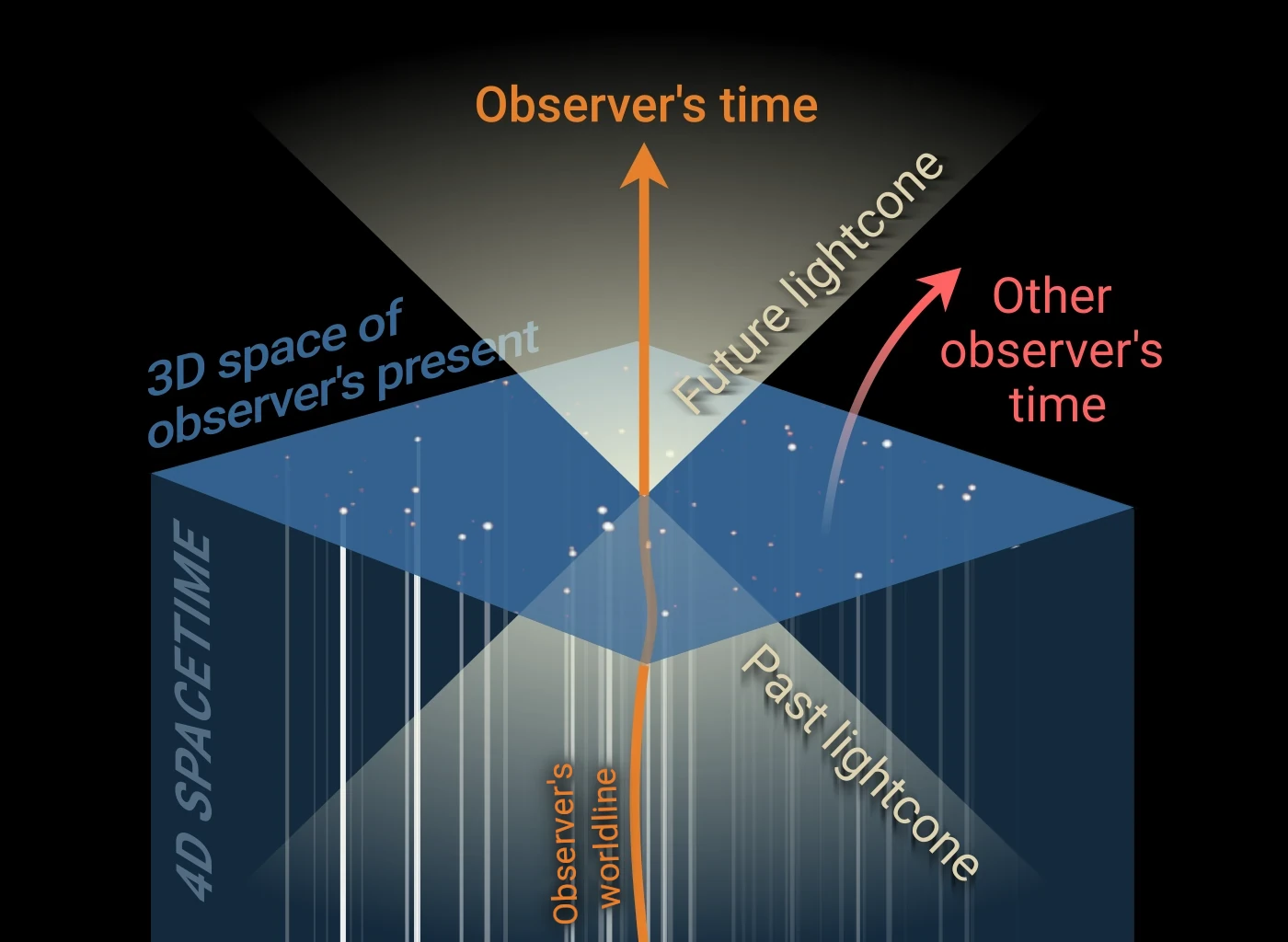

When dealing with objects moving at speeds close to that of light, one must take into account Einstein’s theory of special relativity, which becomes essential in such regimes due to the finite nature of the speed of light. Special relativity regards space and time as interwoven parts of a four-dimensional entity known as spacetime, with the speed of light setting an ultimate bound on how fast information can propagate (cf. Fig. 3). Furthermore, if the objects in question are very small, such as particles at the atomic or subatomic scale, the principles of quantum physics must also be incorporated. Situations involving small, high-energy objects, as typically encountered in particle physics, therefore require a framework that is both relativistic and quantum. Such a framework is provided by relativistic quantum field theory (QFT), developed between the 1930s and 1970s.

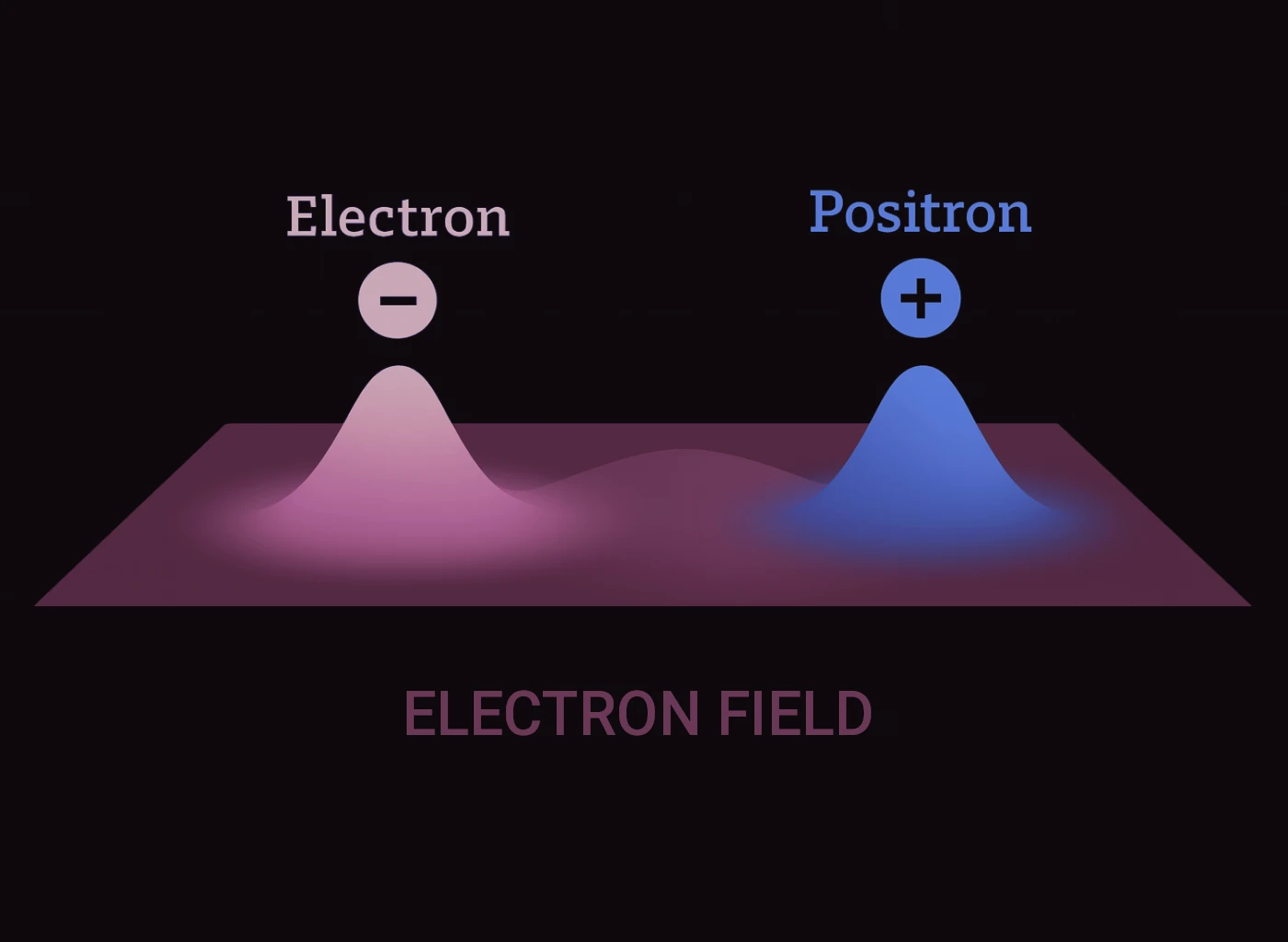

A relativistic theory must treat space and time on an equal footing. In quantum physics, this requirement naturally leads to the introduction of quantum fields – entities that permeate all of spacetime and serve as the building blocks of both matter and fundamental interactions. In this framework, particles are no longer fundamental objects (as they are in non-relativistic quantum mechanics), but rather localized excitations, or “ripples”, of the underlying quantum fields (see also the illustrative sketch in Fig. 4). As a result, particles can be created and annihilated, a phenomenon that arises as a necessary consequence of combining special relativity with quantum principles.

Mathematically, quantum fields assign so-called operators to each point in spacetime. Operators are mathematical objects appearing in quantum physics, formally representing a certain action that is performed on the quantum state. Physically, this action expresses either a certain modification of the quantum state, corresponding for instance to the creation of new particles, time evolution, or specific measurements, through which one can access physical quantities of interest. As such, operators act on the Hilbert space of states. The general principles of quantum physics provide rules for computing the probabilities of measurement outcomes – or, more generally, the values of observables, meaning physical quantities that can be measured in experiments – as stated by the Born rule mentioned above.

One important class of observables is given by correlation functions, which describe how two or more operators are linked by the way the quantum system evolves. Roughly speaking, these tell us how strongly two events in a quantum system are connected – for example, how the measurement of one quantity influences or depends on the measurement of another, possibly at a different place or time. Relativistic quantum field theories implement the principles of special relativity by construction. As a result, this entails that two operators located at points separated so far that no signal travelling at (or below) the speed of light can pass between them act on the Hilbert space completely independently. In mathematical language, they are said to commute. This principle is known as causality.

In general, from the knowledge of correlation functions, one can extract transition probabilities from one state to another, which govern, for instance, interactions between particles. Some of these functions correspond to physically measurable quantities and can be directly compared with experimental results – for instance, data obtained from particle colliders. This is how specific quantum field theories, like the Standard Model of particle physics, are tested against empirical evidence. The remarkable success of the Standard Model stems largely from its ability to predict a wide array of correlation functions with extraordinary precision – in excellent agreement with experimental observations.

Quantum Symmetries and Their Anomalies

As discussed in the previous part of this blog series, symmetries in classical physics are transformations that preserve a system’s dynamics. In quantum physics, symmetries act on the Hilbert space of states – in other words, they are represented by operators – in such a way that they map valid quantum states to valid quantum states, preserve Born’s rule (which governs the probabilities of measurement outcomes), and do not alter the system’s quantum dynamics.

For Advanced Readers: Wigner Theorem

Just as in classical physics, and for the same fundamental reasons, the symmetries of a quantum system often form a group under composition. In quantum field theories, symmetries include spacetime translations (i.e. spatial and/or time translations) as well as internal symmetries – for example, the (approximate) flavour symmetry of Quantum Chromodynamics (QCD), the highly successful theory describing the strong nuclear interaction. This symmetry underlies the classification of hadrons, the composite particles made of quarks and gluons.

Symmetries have profound implications in quantum field theory. As in classical systems, symmetries can generate new physical states from known ones. However, in quantum physics, symmetries do more than that: they partition the state space into distinct irreducible sectors that are somewhat decorrelated from one another. Symmetries impose restrictions on the superposition principle, known as superselection rules: superpositions of states belonging to different superselection sectors cannot be experimentally distinguished from a statistical mixture1 of those states.

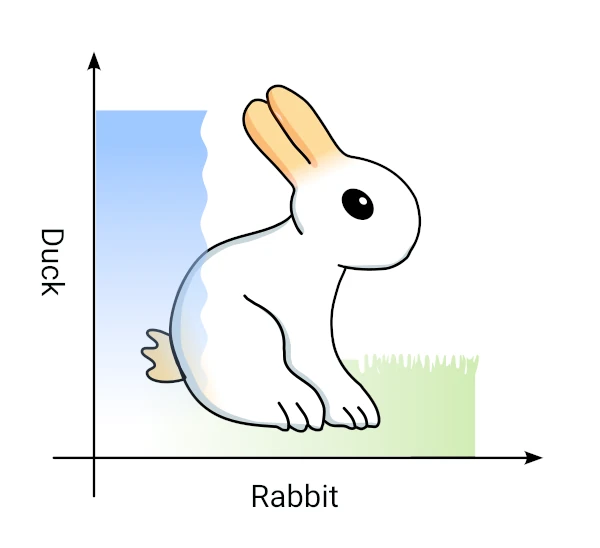

Symmetries also play a crucial role in the classification and characterization of quantum field theories. In some cases, two seemingly distinct theories turn out to be “secretly” equivalent, in the sense that all of their physical observables match exactly. This phenomenon is known as a duality: two dual theories are simply different formulations of the same underlying quantum field theory (cf. Fig. 5 below). Two QFTs can be dual only if they share the same symmetries.

For Advanced Readers: Electric–Magnetic Duality

A profound refinement of this idea emerges in the study of (’t Hooft) anomalies – quantities that characterize how symmetries are realized in a given quantum field theory (see the info box below). Two dual quantum field theories must have the same symmetries and the same ’t Hooft anomalies. Thus, anomalies provide a further powerful diagnostic tool in testing proposed dualities.

Local vs. Gauge Symmetries

The symmetries discussed in this blog post – which generate new physical states from known ones and give rise to superselection sectors – are sometimes referred to as global symmetries, in contrast to another important notion: gauge symmetries (also known as local symmetries). Gauge symmetries, which lie at the core of our current understanding of fundamental interactions (electromagnetism, the strong and weak nuclear forces, and even gravity), are not (global) symmetries in the sense that they do not map physical states to distinct physical states. In fact, gauge symmetries are more closely tied to a particular description of a quantum field theory, rather than to its physical (measurable) properties. For example, there exist dual quantum field theories that do not share the same gauge symmetries.

Nevertheless, these two notions are not unrelated. Starting from a quantum field theory with a given symmetry G, one can apply a procedure called gauging, which yields another quantum field theory where G becomes a gauge symmetry. This procedure is, however, not always possible: ’t Hooft anomalies measure precisely whether a given symmetry can be gauged. In other words, ’t Hooft anomalies are obstructions to gauging.

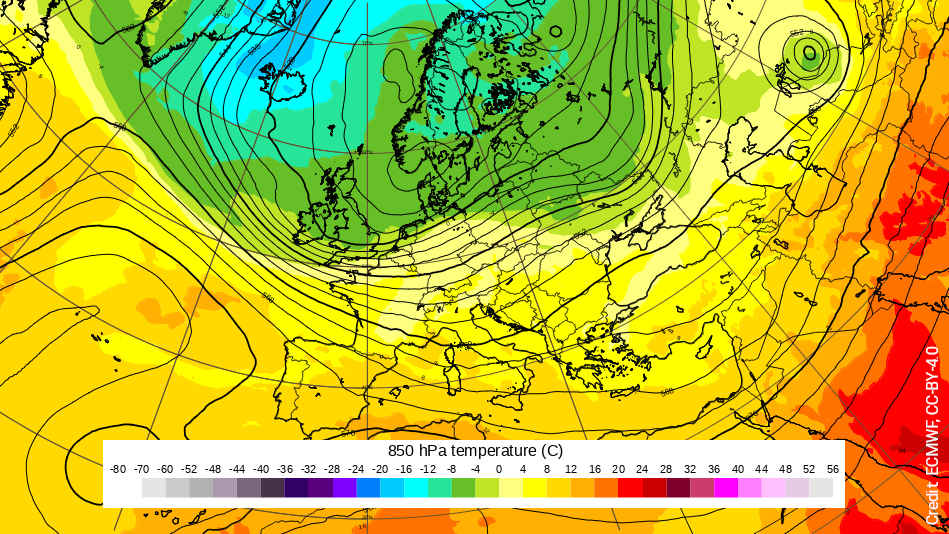

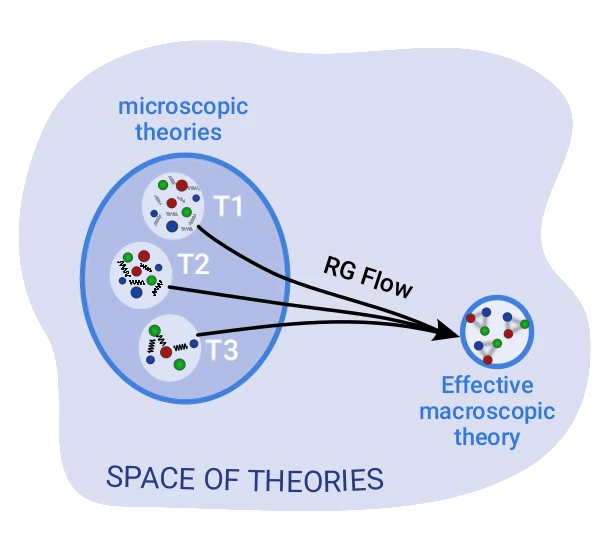

One reason anomalies are so important is that they persist when you zoom in or out to different levels of description. In physics, it is useful to apply different descriptions to a system depending on the scale at which you look at it. For example, at the microscopic level, water is a collection of H2O molecules bumping into each other. But at the scale of a glass of water, it proves far more useful to think of it as a continuous liquid, described by the rules of fluid dynamics. This is called an effective description, and the phenomenon that the most accurate description of a system depends on the scale is known as renormalization (cf. Fig. 6). Most features of a system change as you shift from one scale (or layer of description) to another, but anomalies do not – they persist across every layer. Physicists call this property invariance under the renormalization group flow.

Renormalization plays a key role in the context of quantum field theories. It often bridges between regimes where the quantum dynamics can be studied using practical, so-called perturbative tools (such as Feynman diagrams), and others where such tools fail, typically because fields interact too intensely for perturbative methods to be effective. Quantities that remain invariant under the renormalization group flow are especially valuable, as they provide robust, scale-independent information about the quantum field theory. Anomalies of symmetries are exactly of that kind: they remain constant as one “zooms in or out” of the system, which gives them significant predictive power.

Symmetries as Topological Operators

We have seen that quantum fields in a QFT give rise to (local) operators, which can describe the creation or annihilation of particles at specific points in spacetime. By contrast, the presence of a symmetry in a QFT gives rise to extended operators – operators that, like those discussed previously, act on the Hilbert space of states, but are associated not with points but with extended regions of spacetime (lines, surfaces, or higher-dimensional submanifolds). These regions are referred to as the support of the operator.

Standard (global) symmetries typically correspond to operators that divide spacetime into two regions, allowing us to distinguish whether a point lies in the “interior” or the “exterior.” For example, a sphere in three-dimensional space defines such a separation (with an interior and an exterior), whereas a circle does not. In our four-dimensional universe, an example of an interior region can be pictured as a “bubble” of spacetime: all the events occurring within a spherical region of space during a certain interval of time. Operators whose support divides spacetime in this way are said to have codimension one.2 The symmetry implemented by such a codimension-one operator acts only on the local operators located in the interior region, leaving those in the exterior unchanged. This action is related to the topological nature of such symmetry operators, to which we turn next.

Not all extended operators correspond to symmetries. However, those that do satisfy a special property: they depend only weakly on their support. Precisely, if the support is smoothly deformed (i.e., without tearing) in such a way that it does not cross any local operator – so that the set of operators inside and outside remains unchanged – then the corresponding extended operator acts in the same way on the Hilbert space. For this reason, such operators are called topological, in reference to topology: the branch of mathematics that studies shapes up to continuous deformations such as stretching, bending, or twisting (but not cutting or gluing). In topology, for example, a coffee cup is considered equivalent to a donut, since both have a single “hole” (the handle for the cup). For instance, a topological operator supported on a sphere in three-dimensional space could equally well be supported on an ovoid that can be smoothly deformed into the sphere. A topological operator encircling local operators can be smoothly deformed, without affecting the physics, into a collection of tiny (hyper)spheres, each surrounding a single local operator. In this way, the extended symmetry operator can be replaced by the action of the symmetry on each individual local operator.

Topology vs. Conservation Laws

Generalized Symmetries: A New Foundation for Physics

Recently, a new paradigm for symmetries in quantum field theory has emerged. The central idea is to define the symmetries of a QFT as the full collection of its topological operators in the first place. This broader definition generalizes the standard notion of symmetry discussed earlier. In general, a QFT may possess extended operators of various kinds: local operators (supported at points), loop operators (supported on curves), surface operators (supported on surfaces), and so on. Topological operators that are of codimension one (i.e., which divide spacetime into an interior and an exterior region) correspond to conventional symmetries, while other kinds of topological operators define so-called generalized symmetries. Like ordinary symmetries, generalized symmetries give rise to superselection rules and are characterized by their anomalies, which remain invariant under the renormalization group flow, among other physical consequences. Moreover, when generalized symmetries are continuous, they also lead to conservation laws via Ward–Takahashi identities – just as in classical physics, where Noether’s theorem applies.

Unlike conventional symmetries, generalized symmetries do not act directly on local operators. This is because they do not divide spacetime into interior and exterior regions. Recall our example of the sphere, which we used to illustrate ordinary codimension-one operators: a sphere has a well-defined interior, and it can act on local operators, which are point-like objects within that interior. Now imagine a circle instead of a sphere. In three dimensions, a circle does not divide spacetime into interior and exterior regions – in other words, it has no natural notion of “enclosed” versus “not enclosed.” Therefore, if a quantum field theory admits topological operators supported on such circles (or other closed loops), they correspond to generalized symmetries. While such symmetries cannot act directly on local operators, they can instead act on other extended operators, for instance, on other loops. Physically, this represents an action that is not concentrated at a point, but unfolds over the entire support of the operator.

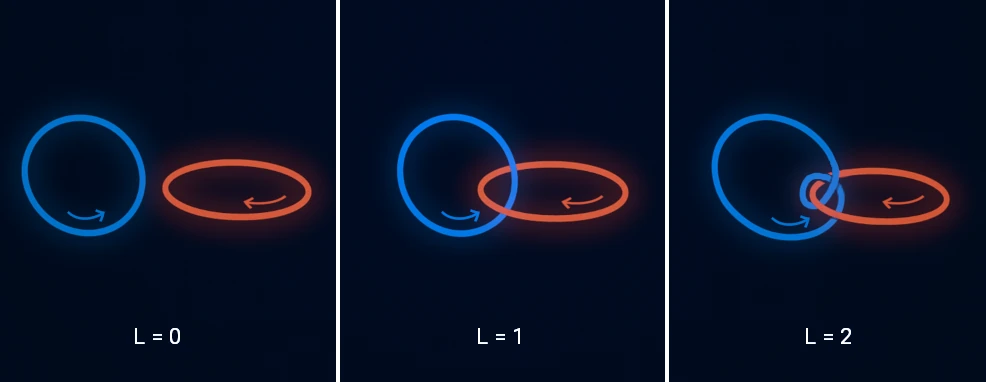

As an example, two circles in three dimensions can link with each other – meaning one loop winds around the other. Mathematicians characterize this using the linking number, a parameter that measures how many times one circle winds around the other. Fig. 7 presents three possibilities, illustrating that the operators are topologically intertwined: one cannot deform a circle away from the other without cutting through it.

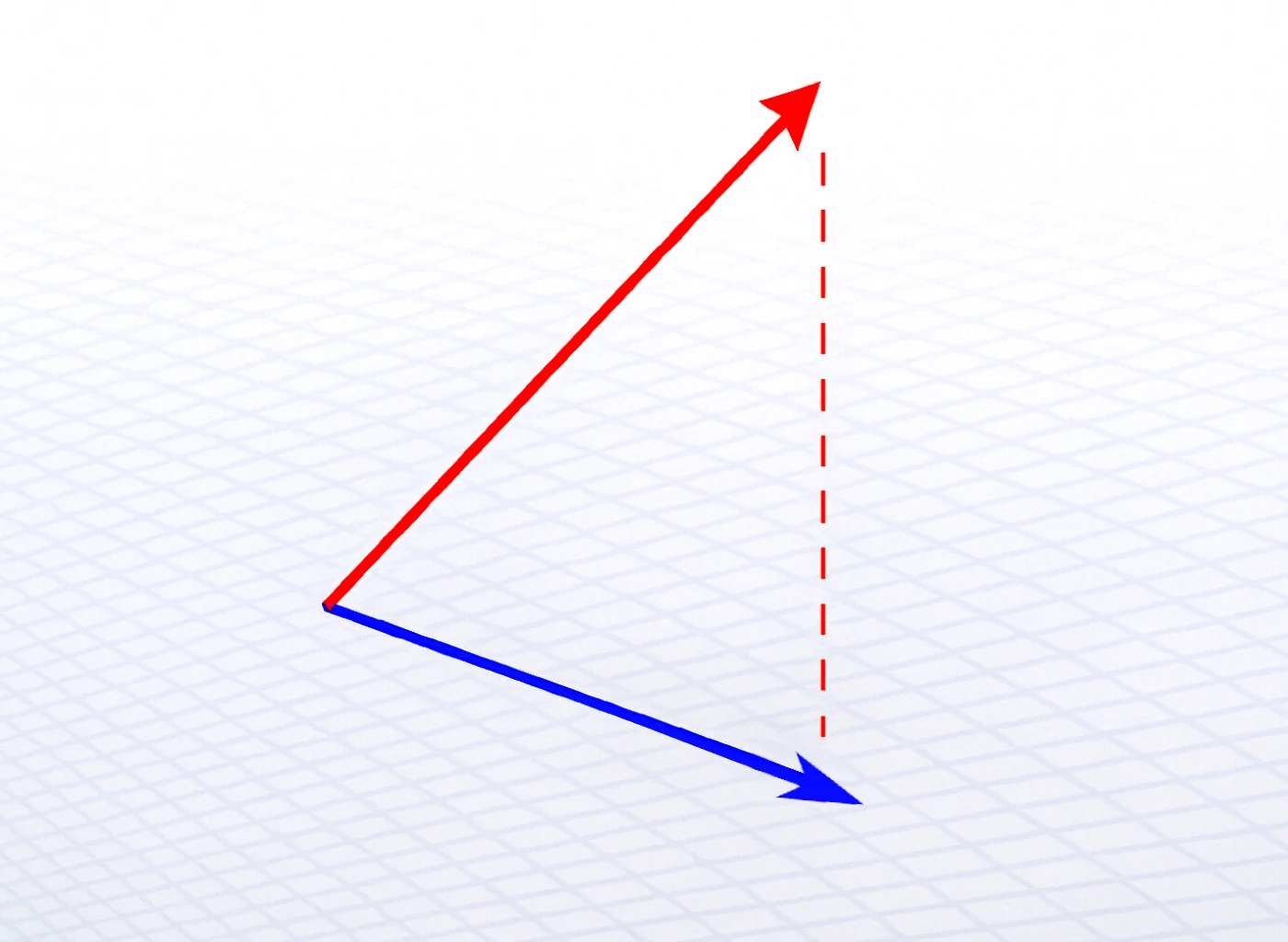

As with ordinary symmetries, generalized symmetries often correspond to groups – structured sets of transformations that can be combined and inverted, as introduced at the beginning of Part I of this series. However, an important restriction arises: the groups associated with generalized symmetries must be abelian, meaning that the order in which symmetry transformations are applied does not matter. This requirement confines us to a much smaller subclass of groups. This strong constraint arises from the way topological operators of generalized symmetries can be “fused”. Codimension-one topological operators (ordinary symmetries) compose only sequentially: applying them in succession yields another operator. By contrast, higher-form symmetry operators are extended objects – lines, surfaces, and higher-dimensional analogues. They can be slid around and brought together to form a new operator, allowing fusions along multiple independent directions.

Beyond ordinary symmetries, quantum field theories often admit generalized symmetries of various kinds. In such cases, a full description of a QFT’s symmetry structure often requires generalizing group theory using another branch of mathematics: category theory, and, more precisely, higher category theory. This typically arises when topological operators of different codimensions interact, giving rise to a “categorical” group-like structure known as a higher group. Moreover, in some quantum field theories, there exist topological operators that implement symmetry operations without true inverses, typically due to interactions between different types of symmetry (topological) operators. This leads to yet another generalization of the notion of a group: fusion categories. The systematic study of these generalized symmetry structures and their physical consequences has been a highly active and fruitful area of research in recent years.

Over the past decade, the study of generalized symmetries has deeply influenced both high-energy and condensed matter physics. It has revealed that many phenomena in quantum field theory, once thought unrelated, are in fact deeply interconnected when viewed through the lens of generalized symmetries. For example, the low-energy phases of gauge theories – foundational instances of quantum field theory – are now understood in terms of the spontaneous breaking of so-called 1-form symmetries, closely mirroring principles used to describe exotic topological order in quantum matter systems. In addition, new anomalies involving generalized symmetries have been discovered in paradigmatic theories such as Yang–Mills theories, leading to novel constraints on their dynamics. More broadly, concepts traditionally associated with ordinary symmetries (including anomalies, dualities, and superselection sectors) now admit richer interpretations within the framework of generalized symmetries. This perspective marks a major step forward in our understanding of quantum field theory, the fundamental language that Nature speaks.

-

A statistical mixture is a collection of quantum states where the system is in one state or another with certain probabilities, rather than in a superposition of them. ↩︎

-

For instance, in three dimensions, codimension one corresponds to a two-dimensional surface, like a sphere; in two dimensions, it corresponds to a one-dimensional curve, like a circle; and so on. ↩︎

Tags:

Physics

Quantum Physics

Fields

Symmetry

Algebra

Geometry

Topology

Probability

Uncertainty

Duality

Groups

Invariants

Correlations